New Manager . . . and a conundrum

Ever had an employee whose motivation--and their subsequent behavior left you . . . puzzled? Have you struggled to find ways to communicate with them, encourage them, even motivate hem to succeed? Ever given up on an employee? At some level, most people who perform well enough to be given the responsibility of leadership expect other employees to act like they do—seek out and perform in a responsible way. When those people do not respond in this way, it can cause confusion for the new leader.

I remember an employee I supervised when I was a young manager. This employee perplexed me. They were, after all, a professional, with a degree, a license, years of schooling and extensive experience. In my “armchair assessment,” I believed that they were competent in their work and, on a human level, I liked them personally. But one thing persistently was a problem with this employee. They simply could not complete their paperwork. Now this, I realize, is not an uncommon problem in health care. In fact, I had already experienced professionals who had trouble getting their paperwork done.

I had experienced already, in my short career, employees that had been put on “improvement plans,” given warnings, or their paperwork addressed through continuous quality improvement programs. Most managers, I believe, have at least one employee they have to consistently monitor and remind about their paperwork in my profession. (Perhaps this problem is exacerbated in the helping professions where "doing paperwork" is often viewed as taking away time from "helping people.") But in this particular employee’s case, even compared to other helping professionals, it was extreme.

I sort of thought I understood what the problem was. The paperwork that was completed, upon inspection, was done to an extreme level of detail. Where my "average" professional would give me a treatment plan with three goals each having two or three objectives each. This professional's plans had 8-12 goals with as many as 20 objectives under each one! I would have been overwhelmed, dreaded starting such a big task, and probably lagged behind and I surmised that this individual needed some external "motivation" to help them get caught up. My method, of course, would be to encourage, communicate, and partner with the professional to get this accomplished.

I made efforts to try and communicate and reinforce elements that could fix the problem. We reviewed the treatment planning process and I emphasized you should have no more than 3 goals with 2-3 objectives. I tracked and reported to each and every professional what paperwork they had outstanding and when it was due. I personally met with this tardy professional and discussed the need to get the paperwork caught up. When this did not fix the problem, I mandated no more than 3 goals and 9 objectives. Nothing worked. the paperwork was not getting completed, I felt stuck.

Of course, not all managers focus on the same things. As a manager, my natural tendency is to try and create "emotional ties and warm connections" in my work groups; the focus of this style is on building consensus, providing support, and valuing openness. It is what William Schutz (creator of the Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation Instrument or the FIRO-B) called "Affection" which he contrasted with a managerial need to express "control" or "inclusion." Since my attempts at creating a consensual response to "getting caught up" was not working, I had to look to other ways of expressing this managerial need.

Relationships and Leading

Before telling you how developing fences or boundaries helped in this situation, I want to draw a connection to the type of leadership that might benefit the most from this construct.

Developing strong fences, and defending those fences, is, I think, an element of expressing control. In Schutz’s definition control is not “being controlling” in the sense of bullying, dominating, or playing psychological games. Healthy control is about efficiency, stability, sustainability, predictability, and good outcomes. I leader high in wanting to express control—a good practice detailed manager—will be hands on in creating systems, procedures, and will shepard the on-going activities to keep them on track. Not my preferred managerial style. Being low in Expressed Control, I want employees to be professional—show up, do the job, and have the freedom to make the job their own—these are valuesI like to “express” in working with employees. To be clear, the best employees, to me, are those that respect boundaries without being told and but strong effort into what is best for the team. But, as leaders we need to grow or become ineffective, and this was a moment where"control was now a factor that I found myself in need of deploying—or I would let this one employee’s behavior hinder the team as a whole.

BTW: Knowing a leader's preferences and identifying what they "want" and would "like to express" as a manager (with a tool like the Firo-B) helps identify common challenges this style of leader will experience. For leaders whose managerial orientation leads them away from a "control" stance to foster an environment of inclusion and/or affection, maintaining good boundaries--fences if you will--and seeing those fences as a beneficial tool and not simply an uncomfortable or even harmful behavior is a challenge. But, even the most affiliative manager, if he has the courage to face it, will recognize the need for control at times.

Setting Boundaries

Ultimately, this delimma led me to a follow up meeting with the professional. The purpose of the meeting being to set a boundary (establish a fence) on the paperwork issue. I started by stating the problem (paperwork was not timely), then we established a clear target (completing the oldest treatment plan), added a timeframe (on my desk by Friday at 5 pm) and the resources to accomplish it (you can delegate or ignore other duties as needed to complete this task this one time).

The result? . . . no treatment plan on my desk by the deadline.

What I did get was a message promising to get it done ASAP. Not good enough. The end result was another uncomfortable second meeting. I clarified what we had talked about the week before, asked for an explanation of why the target was not met, explained the delimma I was facing (not doing my job if I ignored this problem), and asked for input. The professional, after this was all laid out simply said, "I'm not sure I can do this job." My response? A sad (remember I think in affiliative and collaborative terms) confirmation, "I'm not sure you can either." I pointed out that we were now at a point where I would have to continue take formal action ("writing up" a formal poor performance plan) and if he could not bring his performance into line with the expectations . . . that it could result in eventual termination.

The professional chose to resign.

The fences or boundary setting succeeded (in terms of resolving the issue) where my earlier approaches had failed. Yes, I felt bad. In my “dream world” as a young manager, I thought I would always be able to motivate, encourage and support people to success. In the real world, it turned out that it was not all up to me. The hardest "shift" in thinking for me was to see how these fences were actually helpful to people—unidentified problems are likely to be ignored and persist. Allowing someone’s poor performance to create resentment for them among their team members and not honestly challenging the employee is, at best dishonest, and at worst, something that is anathema to most people . . “just tell me the truth” is a common value for most people.

If you are struggling with this idea of setting boundaries and the need for control, ask yourself, "How would this have ended, if I continued to simply try to encourage and motivate this employee?" There were many possibilities, many of which were unpleasant for one or many members of the team. The team itself could continue to become increasingly angry at the underperforming peer . . . and the supervisor. Team members could “escape” the situation and resign. The employee and/or the supervisor could face potential firing for incompetence. The agency, due to the incomplete documentation and effective controls, could lose it’s accreditation due to poor performance on audits. Community funding for the program could dry up—especially if the accreditation was lost. Maybe others as well?

Boundaries and protecting people?

How did this boundary setting protect people? Several ways, including:

the professional avoided being fired (they resigned)

my role as the supervisor was not placed at risk

the team, who were aware of the deficiencies of their colleague, saw that the organization was serious about timeliness being an important aspect of providing our services to clients

the professional was able to negotiate the terms of his leaving (although completing the paperwork was a condition that had to be met)

the paperwork did get completed (they brought last batch in when picking up final paycheck)

the company was protected from liability issues, losing accreditation, funding or facing fraudulent billing accusations

the client was "best served" by the files containing all the necessary information for treatment, referral, or historical record purposes

Leaders need to step up and set appropriate boundaries. This also means that the leader, at times, will need to “be the boundary” or enforce the need for the fence being in place. It is a great irony that those who need to have boundaries set are the very people that do not get the need for the boundaries in many cases. Think of it like this, you don’t need a fence with a good neighbor; you need a fence with a neighbor who does not naturally respect their own, and your, boundaries. Remember, employees lie to themselves. People with boundary problems often shift the focus of the problem to something outside of themselves—thus perpetuating the problem unless stopped by something outside themselves.

New managers, especially those who want to express their leadership through terms of affection rather than control, are particularly at risk for trying to continue the tried-and-failed approaches to motivate employees that are underperforming . . . and there by, exacerbating the negative impacts on their team. Like a football team that needs to “establish the run” so they can open up the playbook and get their passing game into high gear, these leaders need to see setting and enforcing boundaries as tools that allow for, and preserve the ability to maintain, healthy relationships within their team. Only then, can the team function to it’s fullest capacity.

A P.S. for Family Business, Non-Profits, and Ecclesiatistical Bodies

This need to develop good "fences" is especially tricky when the organization or business has an emotional component beyond a typical business venture . . . partnerships, ecclesiastical bodies, non-profit service organizations, and family businesses struggle on other levels that a "typical" business venture does not. In these circumstances there is a critical need for help from professionals who understand human systems.

Available eBooks:

Private Practice through Contracting: Decreasing dependence on insurance.

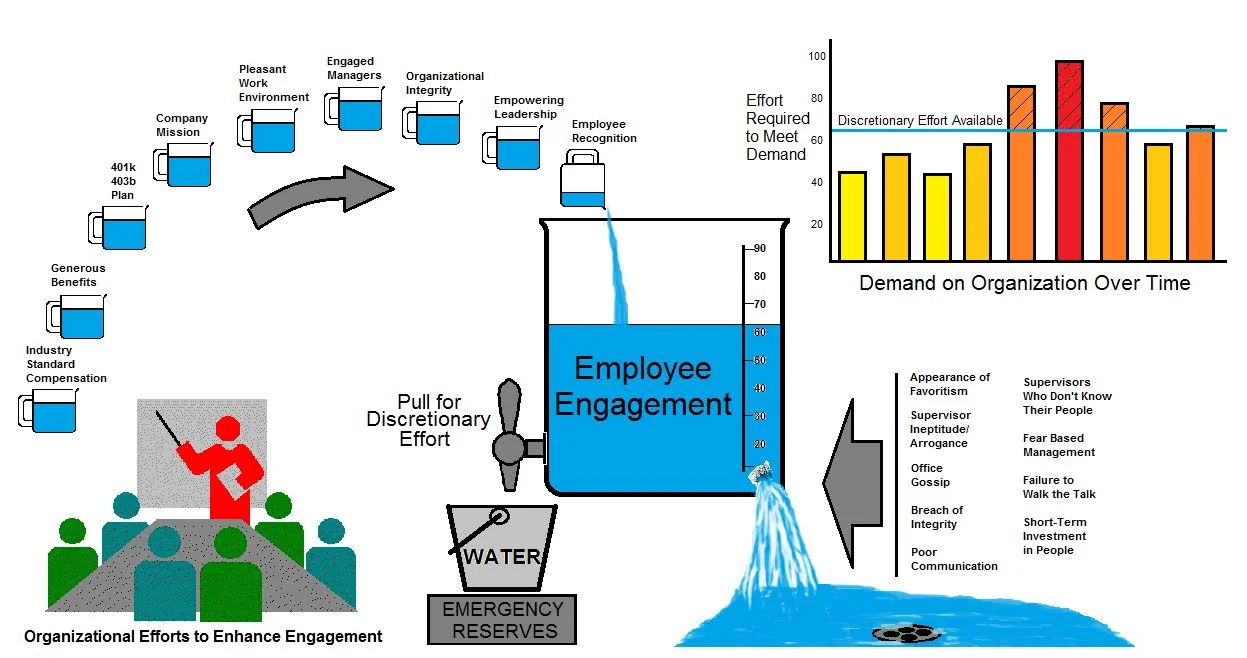

Engaging Your Team: A framework for managing difficult people.

Family Legacy: Protecting family in family business.