The Who . . . Wikipedia

“Who are you? Who, who, who, who? I really wanna know.” Lyrics from The Who, 1978

Employee Retention: a Critical Threat

First, some things remain constant. For example, younger workers, as they have always done historically, will continue to resign at a higher rate than older workers. Industries dependent on a younger workforce will continue to face turnover pressures compared to those with an older average age. However, market and societal changes have brought changes in employee behavior that will continue to present challenges in 2020.

In general, leaving a job continues to be a product of two factors: 1. Employees increasing their pay; and 2. Opportunity for growth. (See a recent CNBC Make It article)

“The reason people are quitting today is because the labor market is so competitive that the only way they can get a significant increase in income is by quitting and going to another job.” Brian Kropp, V.P. of Gartner as quoted by Abigail Hess

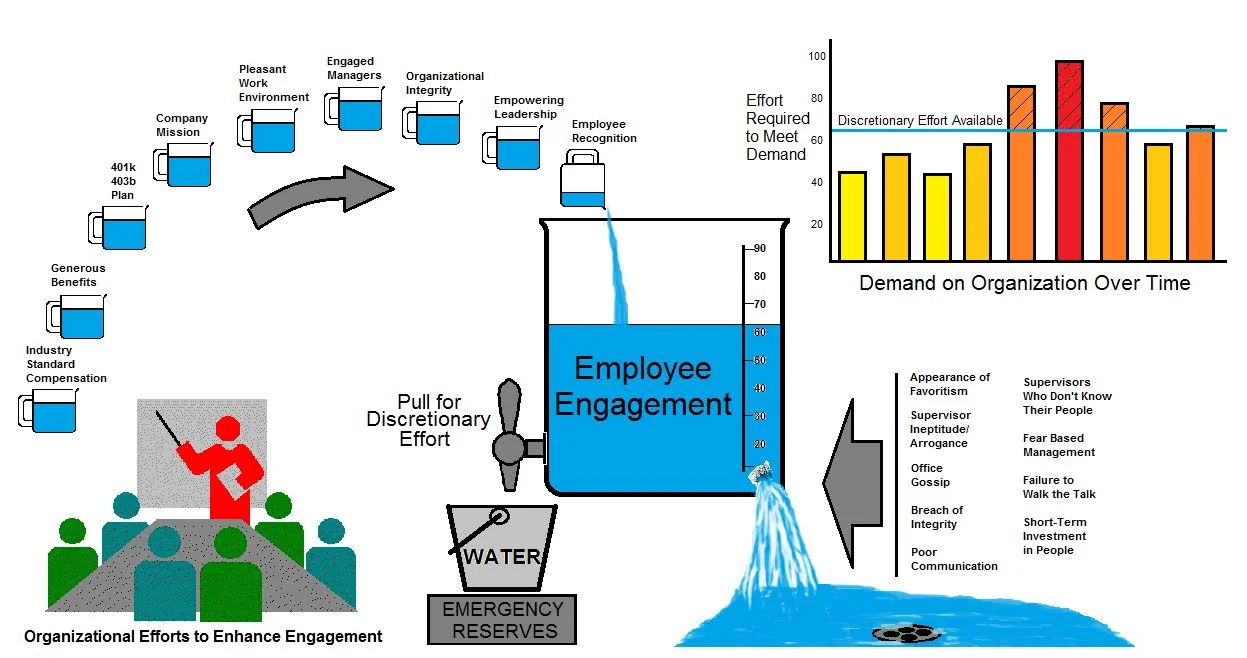

With the old business adage that employees ”join organizations but leave supervisors”— managerial effectiveness, developing employees, active leadership, and guiding change are critical tasks facing organizations in 2020.

While the fading “Baby Boomer” cohort may continue to demonstrate some loyalty to organizational “brand” and riding out their careers with their current employer, younger cohorts increasingly see job changes as desirable for economic or lifestyle preferences.

Those lifestyle preferences may be personal or, increasingly, corporate.

Questions to Address Retention

Three Critical Questions Leaders Can Ask Themselves

What kind of an organization are we?

Who are we likely to attract as employees”

How can we use this “brand” to retain employees in 3030?

Some organizations lean toward achievement, high compensation, opportunity and success. An example might be McKinsey & Company. Employees are likely motivated by compensation and prestige. Others are service oriented. Employees are more attune with the mission of the organization and their own contribution to that mission. Think an organization like The Salvation Army. Another subset, are “the best available.” Meaning that employees see the organizations as the best opportunity in their location, industry, or specific circumstances. Some are the “zany” cutting-edge, trendy, culture-focused workplaces. A local Pixar-type story.

A Single “Core Phrase” May Identify Who you Are

Think about how your brand is reflected in what is emphasized in your every day work. In my career, for example, the organizations I have worked for could have their “brand” defined by one, specific, succinct statement . . . and it was not the official mission statement! Instead, it was a common phrase heard, repeatedly, in the organization.

“Special place, special experience.”—Small college.

“Customers first.”—Gas Station

“A sense of urgency” —Federal Express

“Community safety net.”—Non-profit

“You eat what you kill.”—Private Practice

I hear similar statements from other organizations . . . often they are “tag lines” in their marketing. Only employees know if these statements truly reflect the culture of the organization.

The coffee’s always on. (Local business)

The way you treat employees is the way they’ll treat customers. (Virgin)

You’re in good hands. (Allstate)

Who You Are . . . will Determine Who you Attract

One organization I am very familiar with was great at attracting members. Their core culture was one of support and acceptance. As a result, they got a lot of “looks” and new members. Unfortunately, they didn’t keep them. Why? I believe, it was because their identity didn’t include a vision for a long-term branding. They were good at being welcoming, supportive, and created a comfortable environment but once members were a part of the organization . . . there was not a clear definition of who the organization was.

The organization constantly tried. They came up with new tag lines and mission statements with regularity. Members were told that they were going to “Hit it Out of the Park” (or a similar phrase) but what was the “It” that we were going to swing at?

Another organization had lofty goals. But the real culture was defined by the CEOs comments which often ran along the line of . . . “We’re not here to have fun,” or similar comments. Intended, I think, to emphasize the importance of the work being done (and perhaps as an excuse for not having a more culture-focused approach) it was clear to employees that the job was going to be “all work and no play” and contributed to a dour, oppressive, and depressed work force.

Among organizations trying to attract milliners it’s often understood that organizations today need to present a community focus or social responsibility element to attract employees. This may, however, rebuff other potential employees.

Being True to Who you Are is Critical for Employee Retention

Knowing how you attract employees . . . can be a key to knowing how to keep them. Why do your employees work for this organization? It’s not a simple question. Leaders often make assumptions about employee’s reasons and how they see the organization. Few really know. They don’t ask.

Engage employees. Find out what really drew them to work for this organization and not another. Use it to help define who you are and, then, lean into that identity. The only reason to not do this is that the identify is a dysfunctional one. Then the fix needs to be systemic—and beyond the focus of this particular post.